Folk new to lean thinking often begin with the elimination of waste. They learn the seven wastes or (these days) eight wastes in Lean Thinking. When the subject of waste elimination comes up on social media there’s always a high degree of interaction (and opinion.) I thought it would be useful to put some of the material on lean wastes and waste elimination into context drawing upon research we have conducted over the years to help organisations and individuals learn how to identify and eliminate waste and what we have learned by doing so.

Background – Removal of Lean Wastes

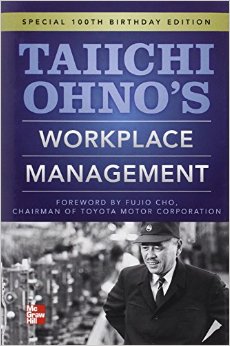

The use of waste removal to drive competitive advantage inside organisations was pioneered by Toyota’s chief engineer, Taiichi Ohno. This waste removal, is productivity oriented towards improving operations so that further wastes are exposed.

However, waste elimination existed before Toyota’s efforts. For example, i his book “Today and Tomorrow” Henry Ford reveals his philosophy of industry. With regard to the nature of waste in industry, Ford suggests that “it is use – not conservation – that interests us. We want to use material to its utmost in order that the time of men may not be lost.” Therefore if something has labour expended upon it, and is subsequently wasted, (“we do not put it to its full value”) then the time and energy of men are wasted. Therefore Ford suggests that “we will use material more carefully if we think of it as labour.” The fundamental driver behind eliminating waste is “true efficiency” which Ford said is simply a matter of doing work using the best methods known, not the worst.

Elimination of Waste at Toyota

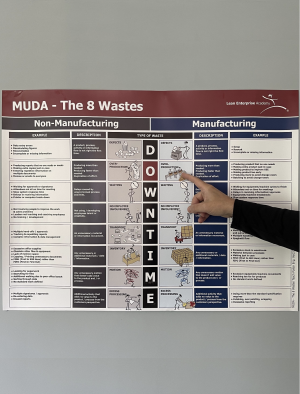

The underlying logic of Toyota’s Production System was eloquently described in the 1977 paper “Toyota production system and Kanban system. Materialization of just-in-time and respect-for-human system.” The paper highlights that to attain low cost production the company pursues “reduction of cost through elimination of waste.” This assumes that “anything other than the minimum amount of equipment, materials, parts, and workers (working time) which are absolutely essential to production are merely surplus that only raises the cost.” In Ohno’s book Toyota Production System beyond large scale production” (pp. 19-20) Ohno describes seven categories (terms from the glossary on pp129 are in brackets) as follows: Waste of

- overproduction (overproduction)

- time on hand (waiting)

- transportation (transporting)

- processing itself (over-processing)

- stock on hand (inventories)

- movement (moving)

- making defective products (making defective parts and products)

Elimination of waste in different environments

Of course, the original 7 wastes came from the environment of production. As researchers and academics realised that waste exists in all processes and activities there was a question whether other lean wastes were more relevant in these environments. In 1998 I co-authored a paper “Waste elimination in lean production – A supply chain perspective” with Chris Butterworth (then a manager at British Steel) as part of the Lean Processing Programme Research we were conducting at Cardiff Business School. The contention was that there were (at least) a “new seven wastes” applicable to production, administration and supply chain settings. The original paper is in the proceedings of ISATA ’98, Dusseldorf with more recent versions in “Manufacturing Operations and Supply Chain Management, the lean approach” (2001.) There’s also a summary in John Bicheno’s “The Lean Toolbox.” The original list is below:

| Waste Category | Nature of Waste |

| Wasted power and energy | Machines and lights switched on when not in operationLeaks on machines, facilitiesInadequate planned/preventative maintenance |

| Wasted human potential | Employing people for repetitive, non value added activitiesNot implementing suggested improvementsNo development/succession plans in place |

| Environmental pollution | Excessive discharges such as chemicalsHigh usage of disposable materials such as packagingLack of recycling policy |

| Unnecessary overhead | Inappropriate trainingExcessive non value added activitiesOver investment for the required output |

| Inappropriate design | Lack of design for manufactureNot understanding customer needsLate design changes |

| Departmental culture | Functional silosConflicting performance measuresLack of value stream management |

| Inappropriate information | Overcomplicated IT solutionsDemand amplificationInformation without a customer |

The waste of human potential

The additional waste that was added to the original seven by lots of organisations was “wasted human potential.” There are valid arguments for including this as a waste or to separate it as a concept as Toyota did. This is highlighted in the original 1977 TPS paper the authors state that there are two basic concepts in Toyota Production System:

- “Reduction of cost through elimination of waste.”

- “Full utilisation of workers’ capabilities.”

Learning about waste and a process to eliminate it

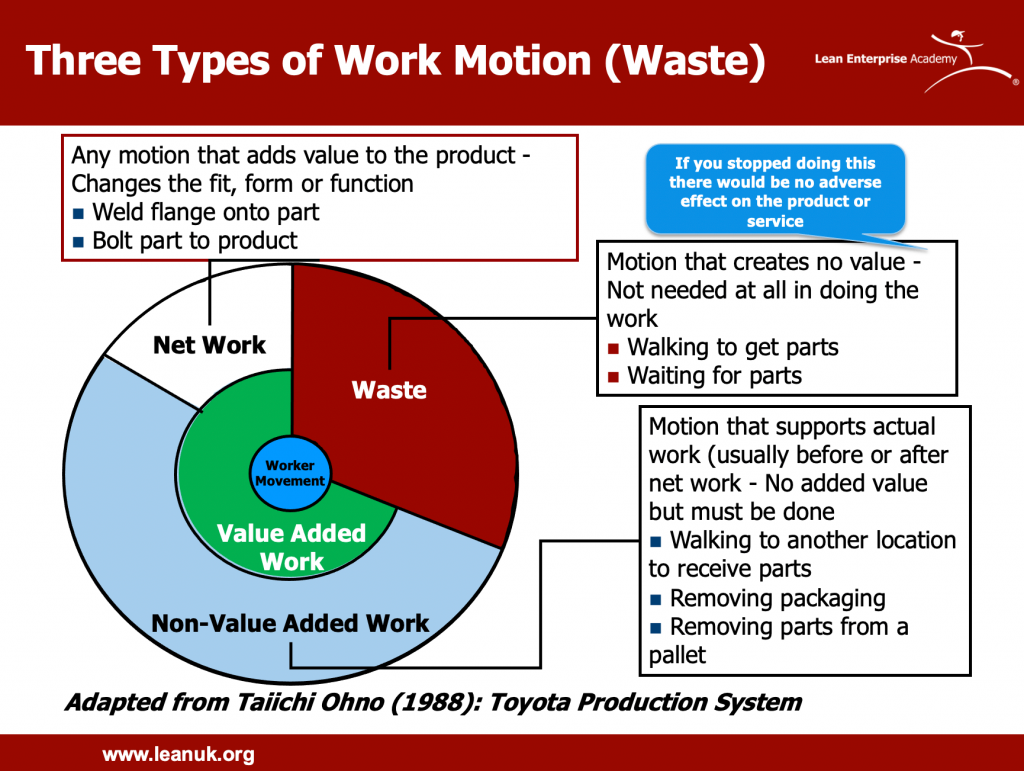

The first step in developing capability in a process or skill is to have knowledge about it. We have done several research activities over the years to understand how to develop capability in a wide range of lean skills more effectively. The research we conducted in the late 1990’s on lean wastes involved categorising each of the steps required to create, order and produce a specific product into three areas: firstly, those which actually create value as perceived by the customer; secondly, those which create no value but are currently required to produce the product and; thirdly, those activities which do not create value as perceived by the customer.

We applied the lean wastes workshop activity to individual organisations and to organisations across a supply chain. We selected a number of personnel from across the value stream, asking them to complete a “Waste Workshop” as shown below in Figure 3.

| · Read each of the sections on the 7 wastes · Give a score to each waste that you believe is applicable to your organisation · You have 35 marks to allocate to the 7 wastes · The maximum score for any of the wastes is 10 marks · The minimum score is 0 marks Therefore if you believe each waste has equal importance in your organisation, score 5 marks each = 35 marks |

Structured Interviews

Following the “Waste Workshop”, we conducted a structured interview. There are a number of reasons for this:

- It provides the practitioner or researcher with a background to the organisation. This background is useful when using mapping tools with the organisation, when analysing and interpreting any data collected in the organisation and also when educating or implementing improvement activities as cultural issues, special causes to problems and one-off events may be highlighted.

- It allows the researcher to meet relevant people throughout the company. This is again of use later when the value stream is mapped.

- This gives people an opportunity to tell you what is wrong. Whilst this is a soft issue, the effects of which are difficult to quantify, it is often useful as the early involvement of personnel to the project can assist with the generation of a sense of ownership of the problems and potential solutions.

- The interviews provide a check that people understand the wastes. This occurs as a result of direct questioning of why particular scores were given and from examples personnel give to illustrate particular wastes in their work environment. A noted weakness of the first part of the methodology is the possibility of respondents’ not understanding the wastes and their relationship with the work environment. As a result the interview process can be used to check this understanding and further help with coaching as the work is observed.

Knowledge of lean wastes is not enough

This early piece of work resulted in many questions. One that we sought to answer specifically was how to engage people to learn the language of waste elimination and develop capability in practically eliminating it. In this piece of research we took 50 people, 25 in site A and 25 in site B. We conducted an “Introduction to Lean Thinking” and followed that up with waste elimination in the workplace in both sites. We tried to carry out the same process as far as the composition of the workforce, the areas we looked at and the duration of the activity.

In site A we used Toyota’s 7 wastes and taught them in the sequence Ohno wrote them in his 1978 book. In site B we taught the 7 wastes and used the acronym TIMWOOD. The question we were seeking to answer was whether there was any difference in recall rates with the two processes. The results are shown below:

| No. of People | Recall after 4 weeks | Understanding | |

| Ohno’s Wastes Sequence | 25 | 16 (64%) | 13 (52%) |

| Wastes TIMWOOD | 24 (1 not present @ interview) | 19 (79%) | 14 (58%) |

The conclusion we made was that the acronym TIMWOOD helped recall after 4 weeks, however “understanding” hadn’t improved in line with the recall improvement. Of course, conducting such “experiments” is fraught with difficulty as we are dealing with people and their individual situations. However, the results were enough for us to suggest that there was an improvement in recall. The unanswered element of this research was how to develop capability in practically eliminating waste? How best to develop “understanding?”

A process for capability development, waste elimination and improvement

We have conducted dozens of pieces of research in how to develop capability. We know that there are numerous factors that improve the likelihood of a better outcome. Examples include leadership involvement, the cadence of checking, the clarity of understanding the problem to solve and the gap(s) to close, the urgency with which to improve and so on. However, what is abundantly clear is that a process is needed to develop capability.

Our current standard (the best way we know currently) from the tests we have conducted is capability development through visual teach posters, with a simple instruction manual to teach the important steps, key points and reasons why. The teaching must be followed up by observation and analysis at the workplace and the cadence must be such that continued practice occurs. The idea that you can do one cycle of activity and then be capable is extremely dubious.

We are always interested in learning about your findings. We think it’s important that we conduct interventions using sound research principles.It’s hard, but we try not to jump to conclusions. Many things won’t work, but that’s where (very often) the real learning takes place and why it is important to conduct research (rather than just jump to conclusions) when teaching people to do lean thinking and practice for themselves.