This article is an adaptation of John Shook’s and David Brunt’s keynote ‘How to Apply Lean Thinking and Practice’ from the UK Lean Summit 2023 on the 19th April. If you would like to watch this keynote, please watch the YouTube video below.

Introduction

David Brunt: John was the first westerner to be employed by Toyota back in 1984 in Toyota City (Japan). One of John’s early jobs was to transfer the Toyota production system (TPS) to their first overseas plant. This was the New United Motor Manufacturing Inc (NUMMI) in Fremont California. This was a joint venture between General Motors and Toyota. John is uniquely qualified to commentate about this transfer to a different culture and environment.

John was also the manager at the Toyota supplier support centre. It is like a sister to the Toyota Lean Management Centre in the U.K. In addition, John was also a senior adviser at the Lean Enterprise Institute before taking over from Jim Womack. He was then chairman of the Lean Global Network. Of course, John also wrote Learning to See and Managing to Learn.

-

Managing to Learn£44.00

Managing to Learn£44.00 -

Learning to See£46.00

Learning to See£46.00

At our UK Lean Summit in April, John Shook and I discussede Lean Transformation Framework (LTF). John couldn’t be in Liverpool in person. We therefore decided to discuss the LTF, rather than have a pure plenary presentation. The LTF is deceptively simple. Five basic questions to ask to gauge how you are doing on your lean journey. We think these are key questions to ask when planning how to apply lean thinking and practice or to reflect on how your journey is progressing. Whilst simplicity is often an end game, there is a danger that people don’t think deeply about the big, simple questions contained in the framework.

We’ve been conducting research using the LTF since 2014, so we started by discussing:

How was the Lean Transformation Framework developed?

John Shook: It is a framework that was developed through a process of thinking about how companies, organisations and individuals can go through a process of embodying lean thinking and this way of working. There are three things we can point to when we describe how it came about.

- Reflections on failure modes and success factors over years of working with and observing many organisations.

- By having a lot of interactions with master lean sensei.

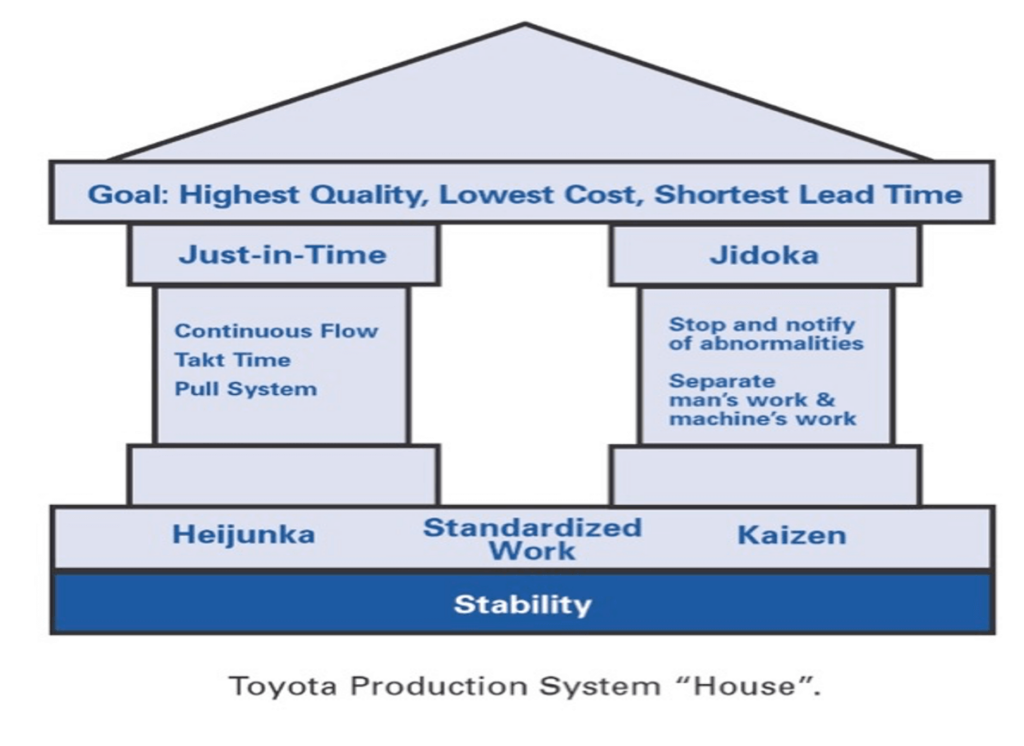

- Reverse engineering the thinking that went into the development of the TPS house. Whether this original one (see image below) or the Toyota Way 2001.

Reflections on failure modes and success factors

The first one is kind of the easiest. It’s the thing that you would think that any of us do or that many of you have done. And what many of you are doing now. Whether it’s regarding your own organisation or your current organisation or others you worked with. You see things that work you see things that don’t work. If we can understand the failure modes perhaps addressing them can help inform us of how we go about introducing or actualising TPS in the real world.

When you get involved in lean thinking and practice or TPS, you fall in love with it! If you give it any chance at all, it will absolutely change your life. We see this, we experience this, and we know this to be true, yet we also see that many people reject it. They don’t give it a chance, then they don’t benefit from the tremendous opportunities that it presents. You can see how this thinking and way of approaching problems can work with anything, including our most vexing problems. Whether applied to our own work or to our organisation.

I’ve had the chance of seeing many successes and failures over the years and as well. Dave mentioned NUMMI, the joint venture between Toyota and General Motors and that is why Toyota hired me 1983. NUMMI was a success. However, I saw what happened after that. General Motors, our partner, had tried to bring that system into its own operations. It struggled mightily and mainly failed miserably, but not totally. But that was just two examples many of us, not only me, have seen over the years. Furthermore, you need break this apart. Try to think about what contributes to success and what are the failure modes that you see time and again. So how can we identify those failure modes? And how could that then inform the way we go about introducing or actualising TPS in the real world.

Toyota itself has always said that TPS was not developed as an idealised model. My sensei back in 1983 & 1984 said the same things. It was not engineered up front. This is what this looks like, this is what we’re going to try to do. Specific situational challenges drove its evolution. It wasn’t named until 30 or 40 years after the development really started. It wasn’t formulated into the house that we all love. I love this house! I probably taught this house more than anyone to huge numbers of people over the decades. But Toyota told us over the years, it is not a matter of implementing these artefacts, it’s a matter of understanding your situation and the problems in it. And that’s what they (Toyota) did and that resulted in something that you can conceptualise as this house.

Reflections on the teaching of a substantial collection of master sensei.

In fact, this takes me back then to the second point. Reflections on the teaching of a substantial collection of master sensei. If you look at what they were all trying to do, say going to a new operation transforming something or forming something from the beginning. The Sensei’s didn’t just say “OK where can I put in any number of the tools and techniques on the TPS house or ones that aren’t shown on it. It wasn’t a matter of putting those in place. It was a matter of understanding the situation and applying certain thinking and then characteristic practice to that thinking.

Reverse engineering the TPS House

David Brunt: So, you used a house metaphor for the LTF. Can you explain why did you not just use the TPS house as it stands. It links to this idea of reverse engineering, right?

John Shook: That’s right. So why not just use TPS and apply it to the situation? Well, I think we are using TPS applied to the situation, by the approach to the situation with questions. Instead of saying where can I apply this tool, you’re asking what does the situation need? This will take you to a very similar place and sometimes very quickly. But when I say we are applying TPS, it’s TPS defined as the thinking production system, not just the Toyota production system.

Taichii Ohno, the developer of TPS said he didn’t want to name TPS at all. Ohno said if we name it, we’ll kill it. Some were calling it the Ohno system, but he said anything is better than that. And they ended up calling the Toyota production system. Years later there was one individual said “think of the T not standing for Toyota but Thinking.” So, the challenge is how to apply the thinking to our situation. Just by looking at the original house can lead us astray. It won’t necessarily and if you work through each of those pieces long enough you will get to the same place I believe. But it is possible to be led astray. To focus only on those pieces – the artefacts. You must get beyond the artefacts and focus on the thinking.

For example, why not just use TPS? Well in the case of NUMMI, we did just apply TPS, that’s all we had to do. We put in everything. We put in all the systems – the product and process were designed in Toyota city and brought over. As well as the people systems and how the management system worked were all brought over and put in place. All the TPS tools – Jidoka, Just-In-Time (JIT), Kanban, Standardised Work etc. were all there, which was okay.

One of my first experiences in trying to reverse engineer this was watching General Motors. Part of my job was to teach General Motors people, an interesting situation. I was hired by Toyota to assist in the process of taking TPS overseas as a whole system for the first time. Something Toyota had never done before. A great source of strength is to recognise one’s weaknesses and they recognised they didn’t know how to do this. So, one small step was to hire one American to work in Toyota city to help figure out how this would work in Fremont, California. Then what we found is that General Motors were able to copy the artefacts quite well.

People have often asked me over the years ‘General Motors had a close up look at this. Why did they not implement this?’ They did – remarkably well. But there were some key pieces they missed. They were absolutely fundamental and essential pieces that they were not able to break. The change was so deep they were not able to bring it into the company. Also, to some degree they weren’t even able to recognise what those changes were. That’s why we developed these set of questions.

Look at the questions and apply them to General Motors. We’ve seen this time and again when we think about failure modes, where a company may be quite successful in bringing in some of the TPS practices in a certain part of the organisation, but the fundamental thrust of that organisation is going in a completely different direction. GM isn’t Toyota. It’s not trying to lead to the same place that Toyota was trying to go. It’s also not informed by the same fundamental philosophies and basically thinking that informed Toyota as it was going through this process.

So clearly then, it’s not strange to think that such a situation would bring about failure. Approaching it through questions is something that we landed on as a key factor. This goes back to my time, especially my last job with Toyota, the Toyota Production System Support Centre (TSSC) where our job was to try to help organisations actualise TPS. I was guided through a study process; I was given an assignment by a master sensei to try figure out the different methods that even inside Toyota different organisations would use to introduce TPS to suppliers. And what that study showed was some parts of even Toyota, would walk in and try to introduce the techniques. And look where can we put in for example ‘Kanban’? or ‘Poka Yoke.’

But there were more experienced Sensei’s that weren’t looking at it that way at all. They would ask what is the fundamental purpose of this facility, this factory, this company? Why is it here? What does it exist for? What value is it creating? And from there what kind of work does it need to do to accomplish that purpose? Then what kind of skills are required and how are we going about developing those skills in our company? Then we could think about what people would want to jump to often, which is the leader behaviours and management system etc.

Sometimes you can go through all those questions and still never take a step back and ask what is our fundamental thinking? How do we think the world works? And how do we think about our existence in the existence of our enterprise? So that’s what the questioning approach tries to accomplish.

Questioning Mind

David Brunt: John you had a couple of points about Questioning Mind, would you like to talk about it?

John Shook: Claude Levi-Strauss was an anthropologist. I was inspired by this notion of what anthropology is which is to look and try to understand how organic organisations and people work in this world. And as Claude Levi-Strauss said “the scientific mind does not so much provide the right answers as ask the right questions”. I think there’s a lot of wisdom in that. If you go back to the scientific revolution of a few centuries ago, what made that revolution wasn’t that we suddenly understood more about how the stars and planets work together, it was because we finally recognised as humans that we don’t know everything. But we have a method that we can use to understand greater. I believe a scientific mind is a questioning mind. Thus, we can approach changing ourselves in the same way.

Furthermore, Nobel Prize winner Naguib Mahfouz said “you tell whether a person is clever by their answers”. I learned eventually how to be able to do things that in my Sensei could do. This was to walk into a facility and quickly see how things should be reconfigured in a lean flow, and how it should look like a ‘lean factory’. But just by giving those answers it can help sometimes. What you’re trying to do is to get at something deeper. That is the second part of the Naguib Mahfouz quote which is “you can tell whether the person is wise by their questions”. I think a questioning approach was worth exploring and it what led us to develop the house.

Questions, Thinking, Action

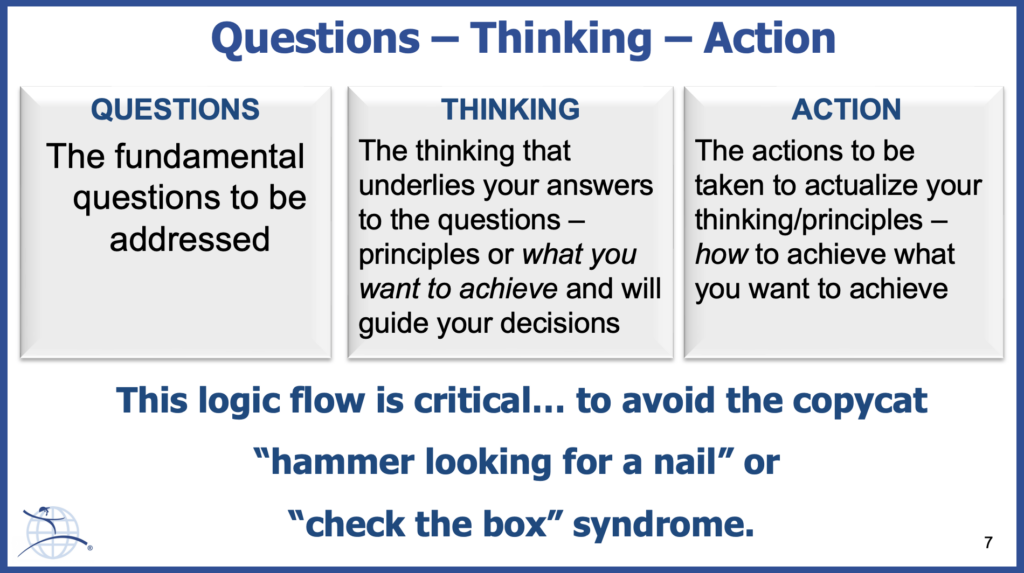

David Brunt: So, a bit more specific; fundamental questions to be addressed, then the thinking that underlies the questions then the actions. Take us through this (image below).

John Shook: This logic flow is important. We had these fundamental questions to be addressed that we came up with. Some of these were not hammered in stone and might be a different set. In a certain situation you could begin in a different way, but underneath that, the thinking production system and what is that thinking and how to get at it? Then finally you get to your situational action which is what you’re going to do to achieve what you want to achieve.

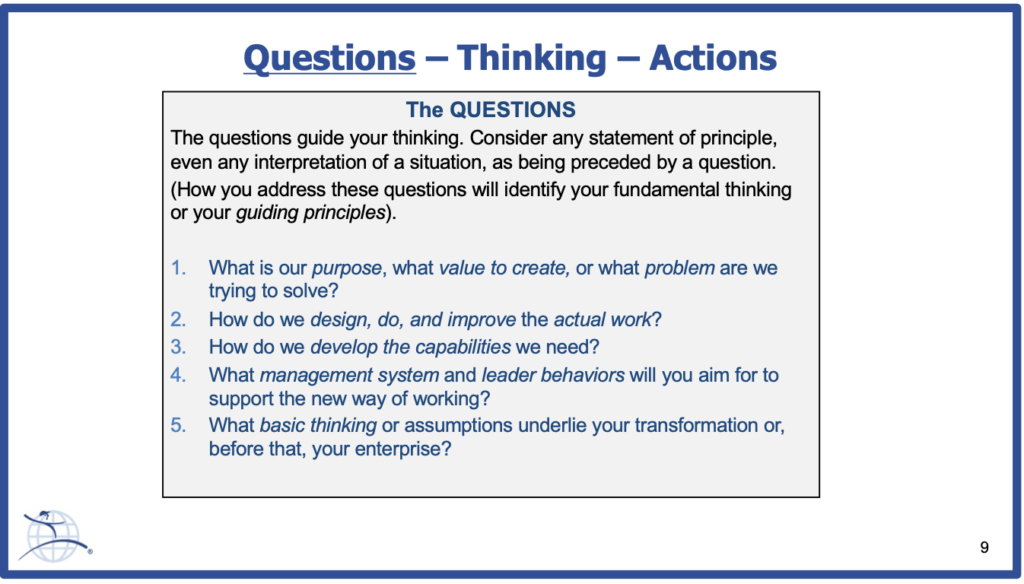

Questions

This (the image below) was a big thing that drove me as we were putting this together. If I looked at failure modes over the years this one has been huge. It is companies and leaders implementing artefacts of TPS and then mandating that throughout the organisation without people understanding why. It was Simon Sinek that said start with why. I’m not sure if you must start with why but you had to get to why quickly a certain point along the way.

This we say ‘a hammer looking for a nail’ or ‘check the box syndrome’ is so rampant. If you look at what a lot of companies have tried to do with lean or with their implementations of TPS that’s what it is. They say they’re trying to be ‘lean’. And they’re going to bring lean into their company as opposed to thinking about what is it, they want to be as an organisation. That is what should come first, I think.

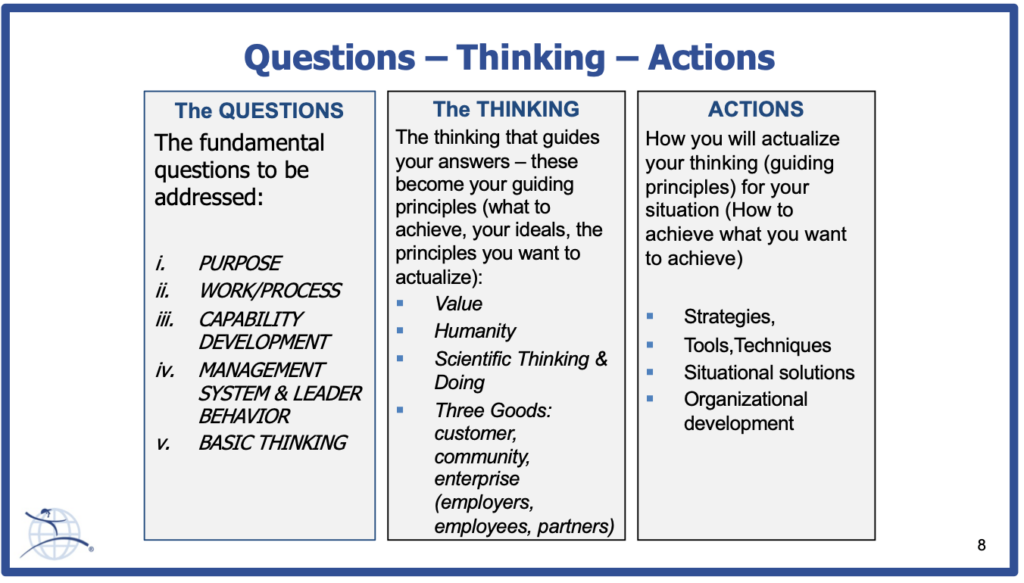

In each of the boxes the questions, the thinking the actions, has underneath it something more specific. So those questions we’ve come up with in these categories, then there’s some underlying thinking. This is just a starter list, it isn’t the full list of what that would be, but then there are the actions. These actions are the things that are more familiar to us. These are the things you can see when you walk into any company, where you can see certain things.

The artefacts are one way to think of it, but the actions that we take. Each of the questions, thinking and actions we have broken down. And these basic questions that we start with, they guide our thinking. I believe I think you can make an argument that as humans our thinking is guided by certain questions. We like to think about first principles, even Elon Musk talks a lot about first principles – but even those come from some form of questions about how things work. So I think we consider any statement of principle, people like to also start with guiding principles, that’s preceded by a question is it not? Or certainly when we try to introduce new ideas to someone, starting with the question can be often an effective way to do so.

The question that Toyota folks use a lot is ‘what problem are you trying to solve?’ We asked that all the time. If we were working on something and making good progress our Sensei would walk in and ask, what problem are you trying to solve here? Sometimes you stop and think, well I’m not sure. Furthermore how does it connect to a higher level, a purpose or strategy? That connects back to Alec Steel spoke about. He was connecting strategy with operations, something that is broken in almost every organisation I see. Then we go straight to how do we design the work, do it and how do we improve the actual work? And that’s one characteristic of lean thinking – we want to understand what problem we are trying to solve and then what needs to be done mechanically, physically to solve that.

After that is developing capabilities so the organisation can do the work that needs to be done, to solve the problem to achieve the purpose. And next what management system and leader behaviours will you aim for to support the new way of working? You could say those are two different questions, but I think they’re still related and we combined them into one.

And lastly what basic thinking or assumptions underlie in your transformation or, before that, your enterprise? And it is sometimes so hard to get at our underlying assumptions that inform how we approach something moment to moment. So this is the first place, this is the first step of this logical flow.

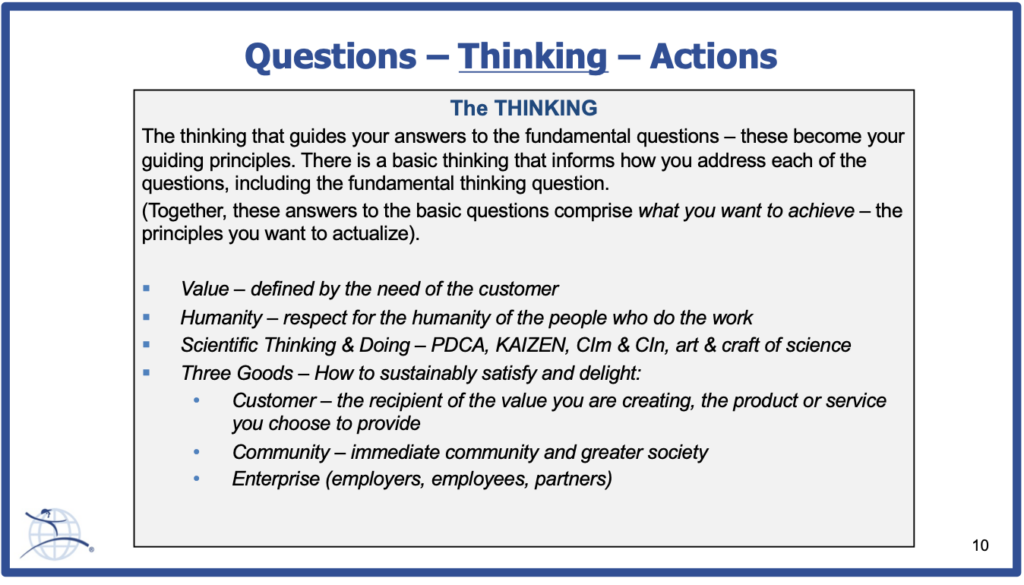

Thinking

In the ‘thinking’ it starts to get closer to the things that we’ve typically learn about or read about when you read a lean book and talks about certain things to do with the thinking like value. This is something that Jim Womack & Dan Jones contributed that was so important with the book lean thinking, which begins with value.

-

Lean Thinking£7.00

Lean Thinking£7.00

Until then the Toyota TPS guys talked a lot about waste and eliminating it. Well, you can’t eliminate waste unless you know what value is, especially if you start thinking about what precedes the factory – design the value first. And this is defined by the need of the customer or what we define in our organisations as ‘what value do I want to provide?’ from their humanity and respect for the humanity of the people who do the work. And we obsess over that. We want to understand the work people are doing. We want to know that it’s being done effectively, but also it is being designed in a way that the individuals who are doing are being given the respect that they deserve.

And then scientific thinking by doing Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA), Kaizen, continuous improvement, continuous innovation, art and craft of science and the Three Goods. The Three Goods was an old Japanese thing going back several years ago which every Japanese executive has learnt from the time they were quite young. This is to think about how we can sustainably satisfy (and even delight) our customer directly, but also the community in which we reside. And now with things so connected that includes greater society and the enterprise, the employers, employees, and partners as well. This gets closer to things that we would read in many descriptions of what the underlying of thinking of the Toyota Way is.

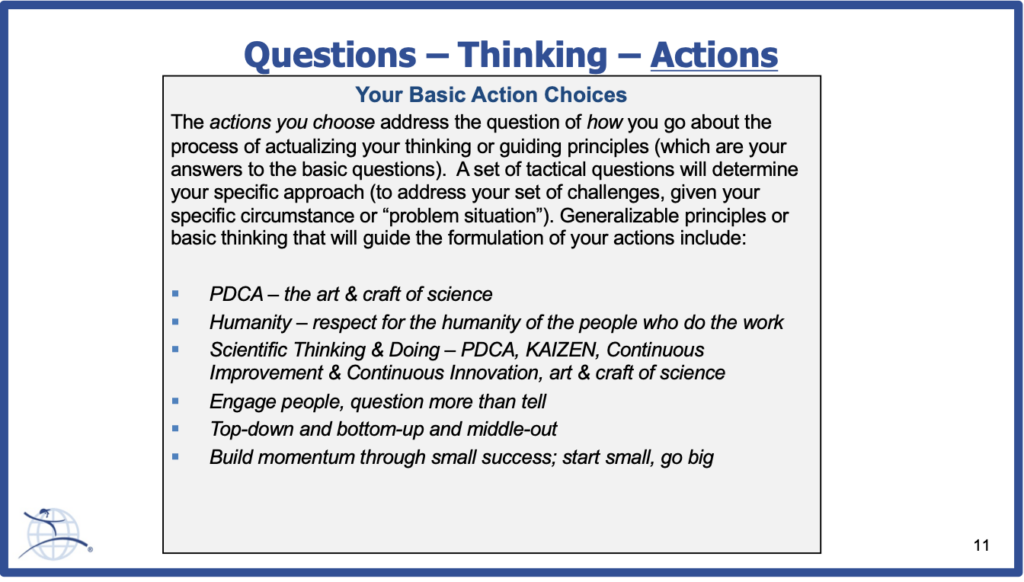

Actions

Finally, is the ‘actions’. This is the fun part where you get more into the tools and techniques, the things that we would do. PDCA is such a wonderful thing and is like the engine that drives lean activity in an organisation. So how do we then embody this idea of respecting humanity in the design of work? How do we become great at scientific thinking, at PDCA, at kaizen. Then you could add more specific things, it could be a very long list!

Then how can we engage people. Again, this idea of questioning. Questioning more than telling. Sometimes you tell, but questioning tends to be a way to engage people more deeply. We can engage their mind and their volition better by questioning most of the time. But it can be top down, bottom up, middle out and very often as we look at an enterprise level. We might build momentum through small successes starting small going big. But that’s just a general rule and isn’t necessarily always the case. So that’s a breakdown of the logic flow, and we’re finding it can help us understand what it is we’re doing in a company, what an organisation is doing. It’s important for individuals. Not just the specifics that they’re learning in terms of tools and techniques but the why behind those and view them as part of an overall system.

What is the Framework and its Purpose?

I think what we can say is this is that the Lean Transformation Framework is “A structure of self reflection to define the gap between the current and desired states of your transformation efforts.” “Self-reflection is critical to creating specific situational approaches that avoid the “hammer looking for a nail” copying.”

So that’s what the framework is and its purpose for the most part, as far as how we use it. Sometimes when we use it it’s not explicit upfront at all. It may be just questions we hold as we think about how companies will go about making the changes that they need to make. But most effectively it is a structure for self-reflection. It is a framework that people can use to self-reflect to define the gap between their current and desired states. It says your transformation efforts, but it could be your formation efforts just as well. So, there’s lean transformation there’s lean formation as well.

I think it is true that self-reflection is critical to creating specific situational approaches that avoid the hammer looking for a nail copying, which is just rampant. As I looked at implementations of lean around the world over many decades, this is just such a common problem and I think it is one that deserves special attention. What do you think Dave?

David Brunt: Yes, I think so. There isn’t just that one thing is a failure mode, there are several others.

A Hierarchy of Questions

The summary high-level questions lead to a next level of questions. Let’s use the example – “How are we designing, doing and improving the actual work?” As you ask this question, it opens more questions. Have you defined the work to be done? Is it being improved? And, if so, how, by what means and what methods? What’s actually happening here is that you’re thinking about lean thinking whilst asking the questions at these different levels.

Then there are also some third level questions. Some of these high and mid-level challenges are defined, and the questions are geared to address the issue in the situation and the gaps to close. In practical problem solving or in Toyota business practices it’s always about trying to think about what’s the problem to solve? And what’s the gap to close?

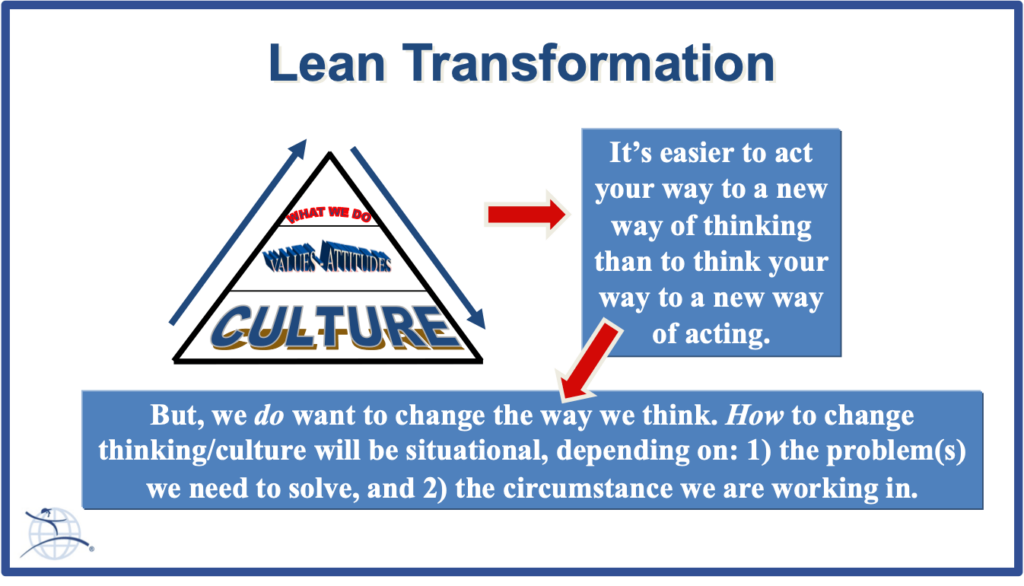

So John, quite often people tell us they want to change their culture. They want a lean culture and ask us how they can achieve that. You have some great thoughts on this which you articulated in a Sloan Management Review article a few years ago. And you use the picture in this image (below.) Please talk us through this graphic.

Act your way to a new way of thinking

John Shook: This goes back to my experience at NUMMI looking at GM and other companies. At the top of the pyramid it is easy to see what and organisation does (“what we do”) and start to copy those things. But underneath all the artefacts, the things we do, there are values and attitudes that aren’t quite so easy to see. Then underneath that is culture or basic thinking. Your fundamental thinking that informs that.

What I found at NUMMI, was that counter to what I had studied in school, studying industrial anthropology, where I thought you would try to change the culture and get everyone on board and then their values and attitudes would become the right thing and they would do the right thing. There’s an opposite way of approaching it that I think is characteristic of lean. This is a learn through doing approach ‘it’s easier to act your way to a new way of thinking then to think your way to a new way of acting’.

However, that does not mean that we don’t want to change the way we think. But we must as it’s a thinking production system. Then you need to how to change our thinking and our culture, and is going to be situational depending on the problem we need to solve. I create software for iPhones, no I build circuits that go into iPhones, I build cars, I work for the government. I’ve actually done some work with the state of Washington government and that’s a different situation. Thus, the circumstances being worked and problems to be solved are quite different. So how you bring the thinking to bear can vary, but then what do we need to do to bring about the change.

Balance between Process and People

We also want to do it with an understanding that we need to have some balance between people and process or social and technical. And its management that is going to balance those based on a solid purpose. If the purpose isn’t set and consistent with what we’re trying to change to, it will not hold. And this is what happened at General Motors back in the day. The purpose of the organisation was not the same as Toyota’s even though they’re in the same industry. Simply trying to paste a TPS like system on top of what their purpose was, with a very different leadership style and management system, did not work. So, we need to align all these things.

Transformation Support

David Brunt: John could tell us about transformation support?

John Shook: Dan Jones said something to to us years ago that I think was really helpful, which is the value of any external support of any lean transformation is determined by what happens after the support ends. I think that’s true. Let’s say I’m a consultant working for a consulting firm and I do some work and I might achieve certain outcomes. But what you can only judge that intervention based on what happens after I leave, after the support ceases. If that’s the case, we need to determine what needs to happen for that to happen. We want a sustaining, self-reliant enterprise to come out of this. Then define those ideal target conditions.

In addition, support should be as little as possible, as much as necessary. Getting that balance right is not an easy thing to do. Very often it is too much of one or the other. Too much support, for example some consulting interventions go in with a whole team of people doing too much, I would say in my view. Other times though there’s not enough support, because it’s true that as many have noted we haven’t seen a wall-to-wall lean transformation go far without the support of some sort of outside sensei. I would like to think that it is possible, but for the most part it seems to be often necessary.

Typical Failure Modes

David Brunt: OK we’ll summarise in terms of some of the failure modes. One of the things we try to do with the LTF is to be conscious about the potential failure modes of applying lean thinking in practice so that we can avoid them. There are lots of potential failure modes, so these failure modes I’m about to share aren’t exclusive, so not least building reliance from the outside would be one of those as well. I’m also always conscious of the as little as possible as much as necessary principle. Some other failure modes that we see frequently include:

- Saying we need to do lean but not being clear on the purpose for doing it.

- Secondly focusing on the technical and ignoring the social or focusing on the social and ignoring the technical.

- Going broad before going deep – the inch, deep, mile wide view vs the inch wide mile deep view.

- Trying to go too fast – Outstripping ability to develop capability vs going too slow and losing sense of urgency and excitement.

- Letting perfection be the enemy of better or settling for better instead of striving for perfection.

- Not being mindful of “culture” or underlying thinking or being overly cautious of “culture”, so it becomes an excuse.

- Losing sight that “lean” is a means to solve problems – At every level (fractal), in every activity.

Sustainable Transformation?

Anyone doing lean should be really concerned about sustainable transformation. Building self-reliance into what we do and being able to do lean for ourselves. That’s what we need to be thinking about. When LEA started approaching this with reference to the Lean Transformation Framework, we recognised that the best examples we ever see are where the leaders take the time to teach and coach their teams. When an outsider leads this it’s questionable as to whether it takes hold.

We have 20 years of car retailers here (at the UK Lean Summit 2023). Pedro Simao is the first lean dealer, in Lean Solutions. Torgeir Halvorsen went to see Pedro Simao and helped his dealership (Torgier) become Toyota’s most profitable dealer in Europe. Torgeir took his team to Sharon Visser at Halfway Toyota in Botswana. These people have all been successful at doing lean. The thing I think is key is that as leaders they taught their teams. They didn’t abdicate that responsibility and they led it.

If this is a critical success factor, then we need learning materials and learning processes that enable leaders to be able to teach their teams. That’s why we we’ve done a lot of work on our teach poster method and on our learning platform. We are trying to conduct experiments to create processes that are simple enough for leaders to be able to teach and coach others.

A Process for using LTF (PDCA)

David Brunt: John, Would you like to briefly discuss a process for using an LTF linked to PDCA.

John Shook: PDCA is so easy to say, but so hard to do, especially on a bigger level and a longer term. There is short cycle (PDCA) which is easier on a given process and how to improve that. Like a scientific method as the way we usually think of it. But it can also cascade up into something that takes longer, that could take years. It can also work at a higher level. So, I think this is simply a way to construct higher level PDCA experiments. I think it’s important to share an example.

A Simple Case – Toyota and Mobility

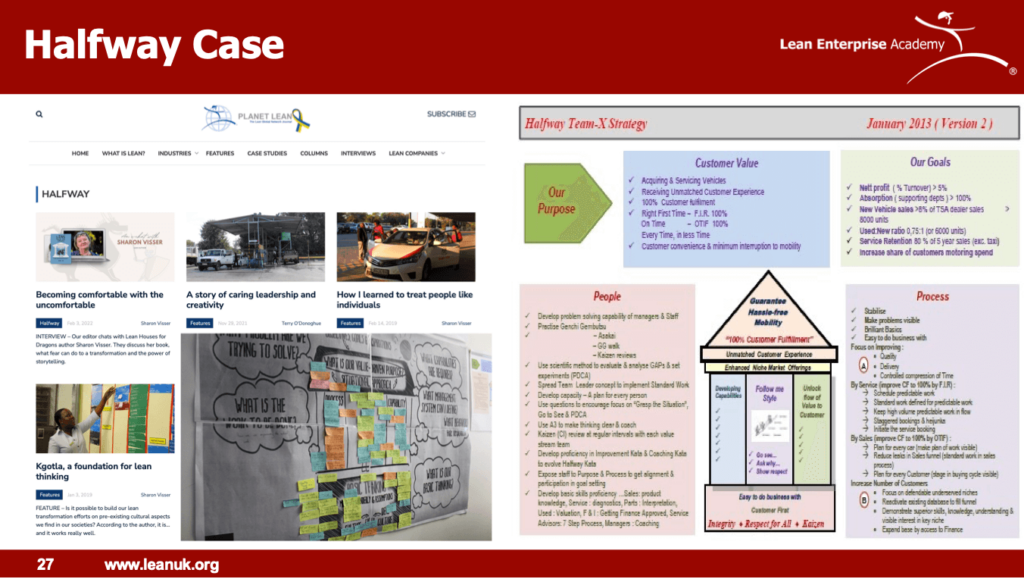

David Brunt: John first talked about the LTF in 2014 publicly and it really resonated so I wanted to try it out. The environment we did that in is with a car dealer. I’ve used car dealers to conduct experiments for 25 years – as a skunk works to test stuff. It works for me because I’ve got good knowledge of the work, I find it easy to understand the work and for the wider lean community many of you interact with a dealer so you art least see the customer facing part of their work. Fortunately the Halfway team were willing to participate in some action based research.

John, talk us through this graphic (see image below).

We developed a process to use the LTF questions to see how we were going in their 8 Toyota dealers. So, there were 8 Toyota dealers, but we didn’t do the same thing in every site, because what we wanted to test things that worked. From this we wanted variables that we kept static and variables that we changed so that we could then see whether there was an impact on those as we went through the change in each site. It was great that they (Halfway) came up with their own version of the LTF, or the Halfway house. And it was this idea of making visible what they were trying to do across all the different dimensions. But there was an interesting takeaway was when we looked across each site some sites did quite well, but other sites didn’t do so well.

Wrap Up

Of course, you need activity on all 5 dimensions to have a successful change, that’s one of the key points of the process. However, the most successful sites have much better alignment vertically between purpose, the management system and their underlying thinking. They are more successful than those with alignment horizontally between the process, management system and capability development aspects of the LTF.

So my challenge to you is to try and apply these five questions to your situation and just see whether you can see where you are strong and where you have gaps. Are you stronger vertically or horizontally? Do you have hotspots things you are good at and not so good at.