This article is a transcript from Dan Jones Reflections on the Lean Movement at UK Lean Summit 2023 on the 18th April. If you would like to watch this keynote, please watch the YouTube video below.

Managing integrated workflows

It’s been five years since I left the lean gemba. I’ve had plenty of time to reflect on what the story of lean may mean for the future. It’s fair to say that Toyota has developed a management system to manage integrated workflow systems and value streams, in a way that other organisations still struggled to do. Toyota did this long before the availability of computers that people assumed would be necessary to manage complex integrated workflows. These systems can take raw materials into finished products, or diagnosis into treatment in a matter of weeks instead of many months.

I would now say quite confidently that these managed integrated workflow systems can beat any system based on utilising assets in performance terms. We don’t always recognise that yet, but I think it’s absolutely the case. This is a staggering improvement in performance that was achieved by Toyota and many others who have followed their example.

You’re right to say that Ford was the first company to create an integrated synchronised workflow all the way from raw materials to the finished product. They did so with a single product and very simplified management structure.

When Alfred P. Sloan came along to build his management system, he ditched everything except the final assembly line which survived. His goal was to create a generic management system. How did he achieve this? By deepening functional and technical knowledge and organising activities by functions and in departments. Central control was achieved by allocating budgets and tracking the utilisation of assets. This led to focussed factories and specialisation of plants around different machines. However, it also led to a search for low-cost labour. This created the global supply chain spaghetti we have today.

Our benchmarking work exposed the wasted effort, materials and costs in these systems compared to Toyota’s system. We also began to describe ‘the carbon footprint’ of the system, which is staggeringly wasteful as well. We’re also just recognising the third form of waste. A huge waste of capital that is happening now.

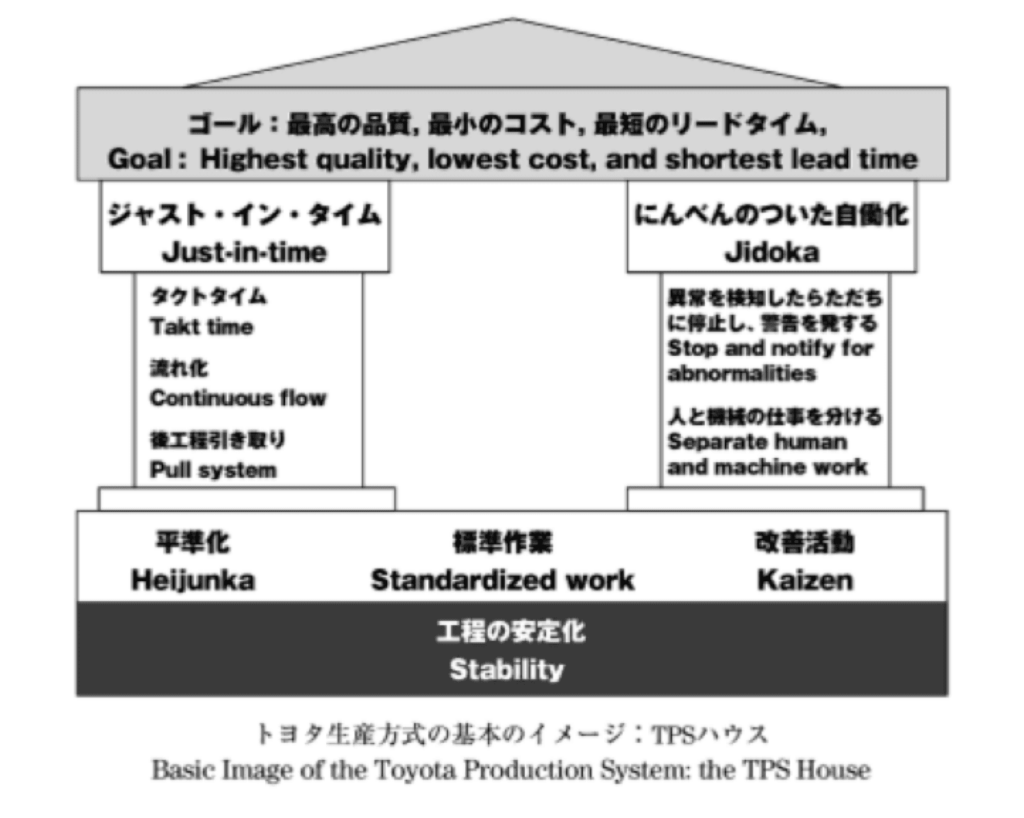

Toyota’s Challenges in Integrating Workflows

The challenges that Toyota faced in integrating workflows were:

- First, developing right size, quick change tools.

- Second, making progress and interruptions to the work visible.

- Thirdly and very importantly, creating the capability of teams to master their work and to address those interruptions. Deepening these capabilities through “learning by problem solving”.

I would also add creating the standard interface between teams through a basic Kanban process, and linking production with demand. A bonus of course is it creates a continuous improvement culture at the same time. If you develop a learning by problem solving system to stabilise the existing system, you also create the baseline for further improvements.

Different Challenges in Different Organisations

In different organisations and different types of work flows you’ll find different challenges of course. In healthcare for instance, you must start with capacity. I’m encouraged that the COVID-19 crisis has unlocked the thinking of primary healthcare care to think about creating the capacity to respond to all the calls that come into surgery every day, then move them all to the next step every day. We will hopefully see this replicated throughout the healthcare system. In short, it’s a different set of challenges but with the same issues to integrate the work. This is because an integrated workflow will deliver far greater performance, rather than simply optimising the utilisation of expensive assets.

In conclusion, the capabilities the of people in your system are critical in making the systems work. When you automate the system without engaging the people, you get far worse results because you automate the current chaos of the flow of work through separate departments.

Making the Continuous Development Process Work

On the development side, Toyotas contribution was to move from the traditional ‘waterfall’ project management into continuous development, through successive generations of product. The Obeya was used to visualise the progress and problems, to create the capabilities of doing simultaneous engineering, set based engineering, all the agile tools, managing the workflow and so on.

But the real difference that made the continuous development process work is the role of the chief engineer. The chief engineer mobilises the resources and the team, and captures the learning from customers, learning from production, learning from engineering, learning from technology about what direction the product family is going to go through.

The chief engineer then sets the direction and makes the very important decisions about what to change and what not to change for the next product generation. This means you don’t upset the stability of the system by changing everything all at once and focus on creating stability again, and a baseline for the next generation improvement. In our times it enables a much faster scale up of technologies, products and so on. This also allows organisations to pursue many alternatives because one size will not fit all.

The third element is Toyota’s leadership. If you think about how leadership is now focused on building capabilities, and not on buying expertise, there is results in a very different decision-making process. That’s where the Find, Face, Frame, Form process really describes the change in decision making, along with the Hoshin dialogue to articulate the gaps and to align the actions towards closing those gaps. Underpinned with a sensei guided development process at every level in the organisation to deepen the experience for solving the next set of problems.

Failure of ERP Systems

These 3 elements; the production flow, the continuous development flow, and the Toyota leadership provide the basics of the lean business system. But there is still some unfinished business, particularly with IT. One of the biggest wastes that I see today is consultants selling ERP systems, to optimise asset utilisation. Selling systems that they hope will turn into a continuous stream of work for them, rather than solving the customers problem.

We know that ERP systems always fail to deliver. Dave Brunt and I witnessed this first hand. We sat down with the CEO of Nestle many years ago, when he complained that he’d inherited the biggest SAP system being run by 9000 employees in 3 different sites around the world. It took two years or more to make a change to that system, by which time the manager reuquesting the change had moved on to another position. So, it simply rigidified the whole system under the guise of improved central control. We have also seen the big systems that were bought in the NHS. They obviously don’t interact with each other because they are not designed to. No consultant really wants to design a system that will interact with competitors’ products!

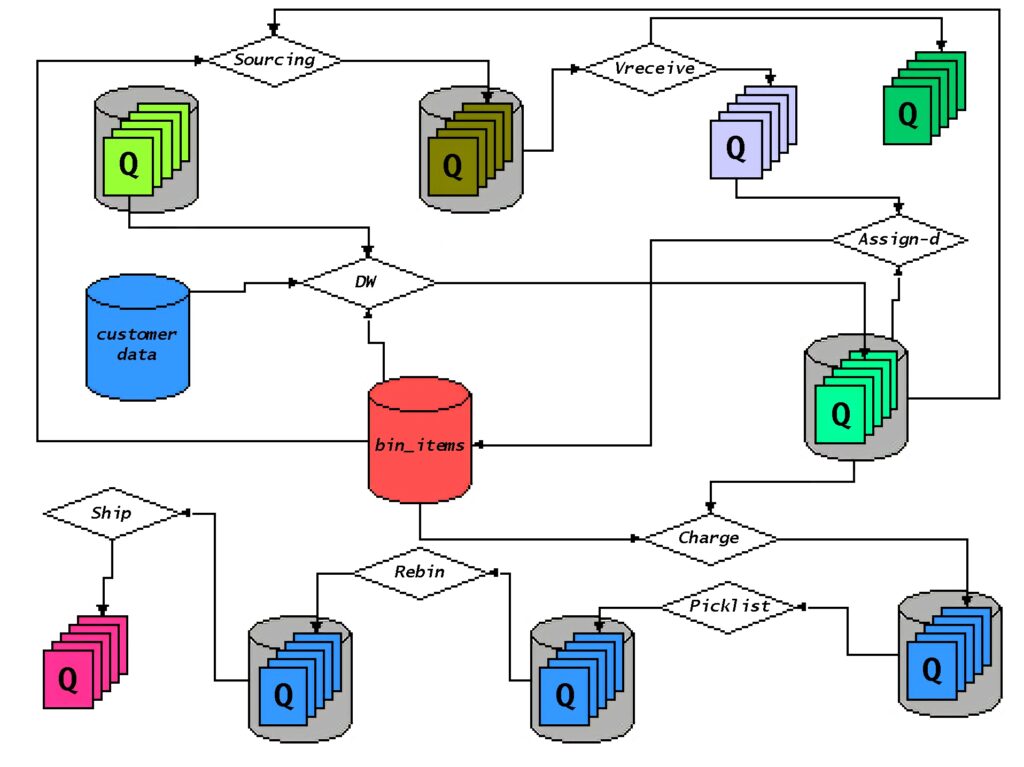

Amazon’s IT System

I’ve watched over the years as availability slumps after the introduction of ERP systems in the grocery and retail industry. Sainsbury’s nearly went bust when I was working with Tesco because of this. The latest casualty is John Lewis which predictably has also faced availability problems after buying a classic ERP system.

There is, however, an interesting example that I’ve come across. It was based upon a very different logic, and that was at Amazon. There are three key elements to the logic behind Amazon’s IT system. The first Bezos’ drive to continually shorten the order to delivery time, despite a lot of resistance from the workforce.

The second is the teams owned their own databases, rather than a big central database with all product information and so on. Third, in a famous internal memo Jeff Bezos said that “teams should only interface with each other through a standard mechanism through a standard interface”, like a Kanban. Distributed responsibility for data and standard interface between teams became the three key foundations of Amazon’s IT system. It allowed Amazon to grow very rapidly into new products and services. Werner Vogels, who was the architect of that system, has just recently published 25 years later his manifesto for distributed computing (read here). The logic behind this system points is completely different from ERP logic and is much closer to an IT system for managing integrated workflows.

Unfinished Business

After Bezos left, Amazon continued to focus on automating every warehouse they could build, as well as building more warehouses. But times changed, and Amazon realised that suddenly they had too many automated warehouses. The inevitable result was to focus on utilising those resources, and utilising full truck loads etc. So, what is happening now? Time has slowed down and delivery promises are getting longer and longer. In many cases, you can purchase a book much quicker from your local bookstore than from Amazon. Thus, Amazon itself is going backwards in terms of IT logic. No consultant has ever taken the Amazon IT system and developed it further. This is because they couldn’t see a business model answer where they can make money out of it.

Yet, there is unfinished business here. I know that Toyota too bought some ERP systems and has been actively looking at the Amazon model (and others) to reconfigure and align them with the Toyota Production System (TPS). I think there are very interesting lessons we can learn from how we create a digital environment and an IT infrastructure that aligns with lean and the TPS story.

Four Conclusions

So, let’s take step back and share a few conclusions of mine. After reading lots (and I’ve had lots of time to read), it seems clear to me that we are living in increasingly divided and unequal societies on the one hand, and a growing distrust of science on the other. I think it’s very worrying and it underlies all our politics, as well as many social aspects of our societies. I draw four conclusions from this.

The changing role of experts

First the role of experts, the dictatorship of experts, is going to change. Instead of the experts being the dictators and dictating how we should work and live, they are going to have to respond much more to the needs of the workflow and the needs of customers. They will also need to work more closely to enable those workflows to deliver the value to customers. There will also be a fundamental change to the role of experts. We’re not going to get rid of experts, we still need experts. However, we need a very different relationship between experts and the people running the workflows, designing, developing and producing products and services.

Jumping to Solutions

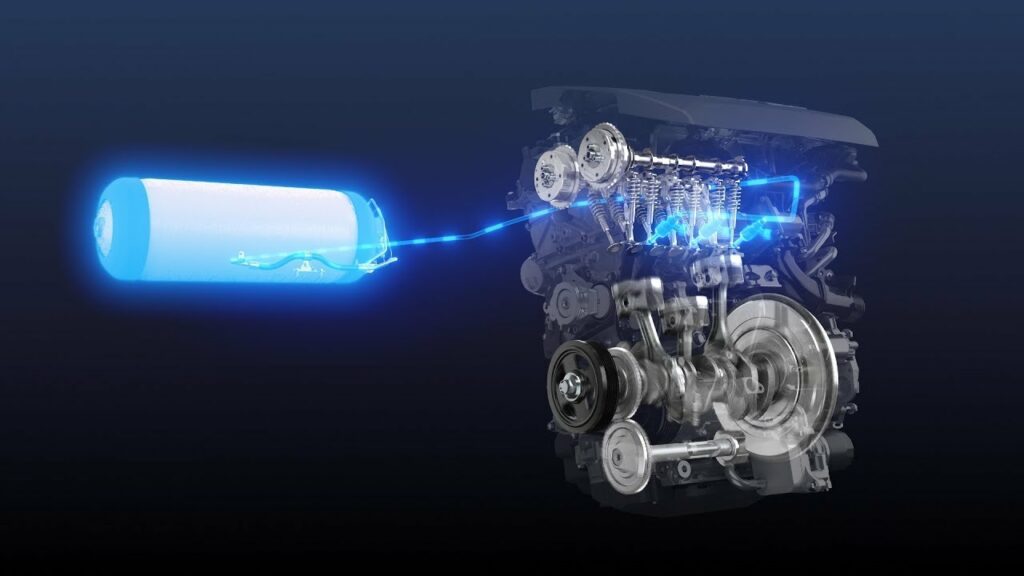

The second is we are prone, and so the environmental movement is prone to jumping to a solution. For example, the solution that everybody is going to be driving electric vehicles, instead of working back from the very different circumstances in which people want mobility. We need to think about alternative technologies that may meet those different needs in different ways. I never thought there would be one solution despite what Elon Musk wants to tell us. Toyota’s approach to exploring alternatives is right. The policymakers and the environmental movement need to recognise this instead of oversimplifying the world and jumping to a solution.

Democratising the Experience of Problem Solving

The third point is democratising the experience of problem solving at work. Doing this will also help us manage our lives better. For instance, many of you will have, as I have got, a long-term health condition that you must co-manage. We also must provide the skills of understanding the data that you’re generating and how to share this with your Physicians/Doctors. We also need to understand how to disentangle all the different potential impacts on your health condition, managing the health condition, managing your lives, and steering your household through challenging times. If you’ve experienced problem solving at work, you’ll appreciate the value of science in helping you manage your lives as well.

Learning by Problem Solving Education Path

The fourth is a much bigger point, learning by problem solving is the education path for everyone. It is not just for those who are not following an academic path. In fact, I think for academics as well. Our education system has been falsely focused on the need to train everybody in academic skills. Instead, we should be thinking about using the Toyota example to create learning by problem solving education systems. This would be for everybody and would benefit everybody. The lean movement has the potential to provide a great explanation of how this would work.

‘Democratising science’ is the way we’re going to create an environment in which people are willing and conscious participants in meeting climate change. Incorrectly seeing lean as just a business improvement tool is a mistake. Lean is a manifestation of a much more powerful set of ideas. Empires come and so do businesses but powerful ideas live on across time and across cultures. We need to understand the underlying ideas behind lean and see where they will apply in wider societal contexts, to make sense of what we’ve been doing over the last 30 years.