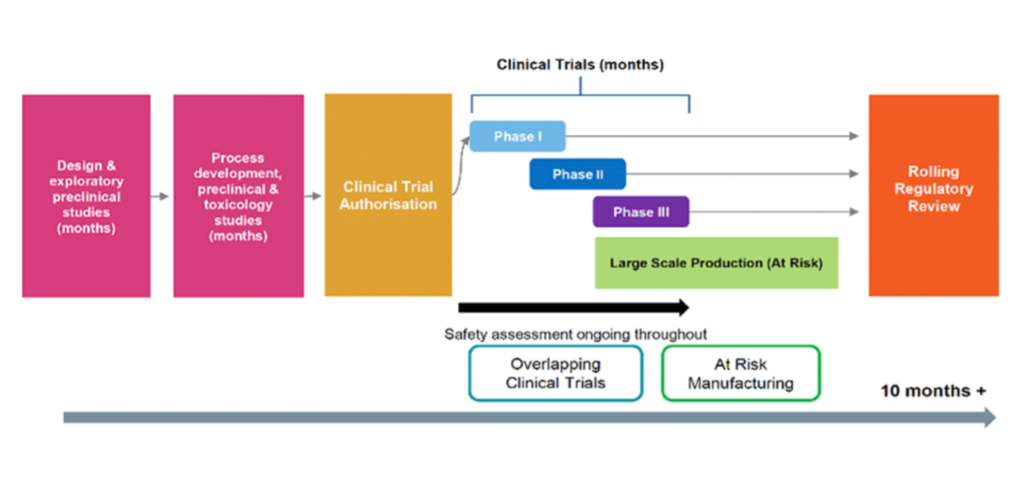

The UK Government’s approval of vaccines in December was great news in the rollercoaster story of the Covid-19 pandemic. Development and approval occurred in record time, helped along the way by some lean thinking (you can read the Pall Story of how lean thinking helped here) and it looks like time compression (which all lean thinkers know about) was applied to the development process by implementing overlapping clinical trials.

However, having a vaccine is only part of the process. Lean thinkers know that

“to properly understand lean production we must look at every step in the process, beginning with the product design and engineering, then going far beyond the factory to the customer… In addition, it is critical to understand the mechanism of coordination necessary to bring all these steps into harmony and on a global scale, a mechanism we call the lean enterprise.”

“The Machine that Changed the World” in 1990 (pp.73)

The quote, written in the land-mark business book “The Machine that Changed the World” in 1990 (pp.73), describing the different business logic being used by Toyota led to the spread of a new, more effective approach to doing and organising work. It is a superior business system and a much better way of delivering value. The question that I asked myself yesterday was whether the logic appears to have been lost on Wales’ First Minister, Mark Drakeford. In an interview on BBC Radio 4 on Monday, Drakeford claimed that using all Welsh stocks of the Pfizer vaccine in the first week would leave vaccinators “standing about with nothing to do” and that would be pointless.

At the Lean Enterprise Academy, we have a history of ground-breaking research. We heard about problems getting vaccines to the front lines and had thought about the different ways we could help. As part of a two-part process to inject lean into the process (pun intended – a first shot and a second shot) we planned a thought piece about how lean thinkers define problems, organise work and develop capability across the enterprise and supply chains.

In the second part, we would go to “gemba” to observe the process. Gemba is a Japanese term. It is used at Toyota to describe the importance of going to the “real or actual place.” Where value creation is taking place. The underlying thinking is to grasp a current situation. Ensure we have a good process. Celebrate the good things and make visible the problems people have. Of course, there will be problems – lots of them, as we are dealing with probably the largest logistical endeavour, we’ve faced in peace time. What is key is to develop good problem solving capability so we can get back to the required standard quickly, rather than blame others for mistakes or issues.

Defining Problems & Understanding Work

It looks likely that Covid-19 will be with us for many years to come. The folk close to the work (in hospitals, hubs, GP practices and pharmacies) have knowledge of vaccinating thousands of us every year all be it on a smaller scale. The question we asked ourselves was how can learning be captured during this process so that the work can be made easier to do? Overburden of the front-line is neither sustainable nor respectful. There must be things that can be done. Kaizen (continuous improvement) will be key.

We recommend that anyone embarking on using lean, answer fundamental questions about their situation (rather than copying solutions from elsewhere) organised around the issues of purpose, process and people:

- Purpose: What customer problems will the organisation solve to achieve its own purpose of prospering?

- Process: How will the organization assess each major value stream to make sure each step is valuable, capable, available, adequate, flexible, and that all the steps are linked by flow, pull, and with demand levelled within operations and across the supply chain?

- People: How can the organization ensure that every important process has someone responsible for continually evaluating that value stream in terms of customer and business purpose and lean process? How can everyone touching the value stream be actively engaged in operating it correctly and continually improving it?

Defining Purpose

In terms of developing and administering a vaccine the purpose appears pretty clear. Above all this must be done safely, with high quality, as soon as possible (for everyone), at the lowest cost. Operationally we talk about Safety, Quality, Delivery and Cost (while developing people.) To highlight problems in any of these dimensions we develop a target condition (what we need to achieve) and compare it to actual performance.

There are different levels of detail published across England, Scotland and Wales. To use one example, in the Wales plan, three milestones are set out:

- By mid-February – all care home residents and staff; frontline health and social care staff; everyone over 70 and everyone who is clinically extremely vulnerable will have been offered vaccination.

- By the Spring – vaccination will have been offered to all the other phase one priority groups. This is everyone over 50 and everyone who is at-risk because they have an underlying health condition.

- By the autumn – vaccination will have been offered to all other eligible adults in Wales, in line with any guidance issued by the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI).

It is debateable whether these milestones would pass a lean thinker’s test of being specific gaps to close. They are not specific. Overall volume is not defined, nor is the mix (the proportion of age groups for example.) The time portion is also ambiguous. Is mid-February the 14th (which in 2021 falls on Sunday) and “by the Spring and Autumn” are even vaguer statements. You can read the reports and a link to the report here. The England plan does at least have a date (February 15th) but volume and mix are not explained.

Processes That Flow

Processes should be designed so they flow. However perfect flow is a very difficult thing to achieve in practice. Lean Thinkers have distinct ways that they look at flow. They have tuned their eyes to check:

- Does the information flow?

- Does everyone know the hourly output (production) target?

- Are we behind or ahead of plan?

- How quickly are problems and abnormalities noticed?

- What is the management system to respond to problems and abnormalities?

In the vaccination process there is clearly an information process – agreeing the appointment, gaining consent to vaccinate, ensuring that data exists on what has been administered (vaccine 1 or 2 of which variant etc), where (right or left arm), when and to who. Does the material flow?

- Does the workpiece move from one value creating processing step right to the next value creating processing step without any delays, backflows, waiting or quality issues?

There are several material flows here. Obviously, there is the flow of the vaccine, the support materials such as PPE and any dressings required. But arguably we as patients are the “workpiece” being worked on. We enter as an un-vaccinated patient and exit as a vaccinated person.

- Do the operators flow?

- Is the manual work standardised so it is repeatable and consistent within each cycle?

- Can the person efficiently go from performing one value creating work step (work element) to the next?

The workers include those taking bookings, those adding patient details to the database, those replenishing supplies and those administering the vaccine.

Lean thinkers have techniques that they use to communicate issues and opportunities. Simple layouts and spaghetti charts show the flow and where stagnation occurs. An example is available here. Value stream maps connect the material flows and the physical flows. But, possibly one of the most mis-understood concepts that appears key to administering the vaccine safely, right first time, on time in the calculation of the takt time.

What Really Is The Demand?

“Takt” is a German word for pace or beat, often likened to a conductor’s baton. Takt time is used to help match the rate of production or output in a pacemaker process to the sales or customer demand rate. In the case of delivering the vaccination on time it is a calculation of how many vaccines we would need to do to vaccinate a subset of the population (or the total number of people eligible) by a particular end date.

The ONS reported that the UK had a population of 66,796,807 people in mid 2019. 13,320,000 of those are aged under 18 and therefore excluded from the Covid-19 vaccination process. Roughly 53,500,000 people are eligible for the vaccine. To understand the rate at which we need to vaccinate we divide the available work time by the customer demand (population.) Of course we must multiply the population x2 as the vaccination method involves two doses.

We started vaccinations of the Pfizer product on December 8th. To vaccinate everyone by 1st September, working 16 hours/day 7 days/week we would have to complete a jab every 0.14 seconds to vaccinate the total eligible population. That’s about 428 jabs/minute or 25,680 per hour or 410,880 per 16 hour work day. Of course there is a ramp up period that has skewed these numbers, but that’s the simple maths.

The takt time calculation also helps us with our supply chain design as we can transmit that beat throughout it. Geography characteristics including drive time (and therefore lead time), population density and demographics are just some of the factors to be considered. However, the initial determinator to how many vaccination centres that are required is the work content to administer a jab. Work out customer demand and the process.

The takt time is the rate we need to vaccinate. The cycle time is how frequently a finished item comes out of the pacemaker process. This would be the time a patient takes to come out of a clinic room or booth where the vaccine is being administered. If the cycle time is greater than the takt time we will have a problem meeting the requirement. If the cycle time is less than the takt time the process will meet the demand all other inputs being maintained.

The key to understanding the cycle time lies in defining the standard work elements to make one piece, or in this case administer one vaccine. This will form part of our second paper – and is done by observation at the workplace. We hope this will be available next week, but our observations are dependent upon vaccine supply. As work elements are recorded, we begin to see waste – work that creates no value but must be done for the current process to operate. Examples include excess walking, waiting, motion, errors, over processing, excess materials and overproduction. The people engaged in doing the work should observe each other and define these work elements, not be subjected to work study by an outsider. Analysing the work, isn’t about working harder. On the contrary, the focus should be on making it easier for workers to provide value for customers. By analysing the work as successive items (or in this case vaccines are given) enables the team to see how repeatable the work is and can be. The aim is to agree a lowest repeatable time – not the fastest time, but the time the workers agree they can achieve throughout the working time and without overburdening them. The outcome of such analysis is an understanding of the total work content required to complete one item (in this case a vaccine from start to finish.)

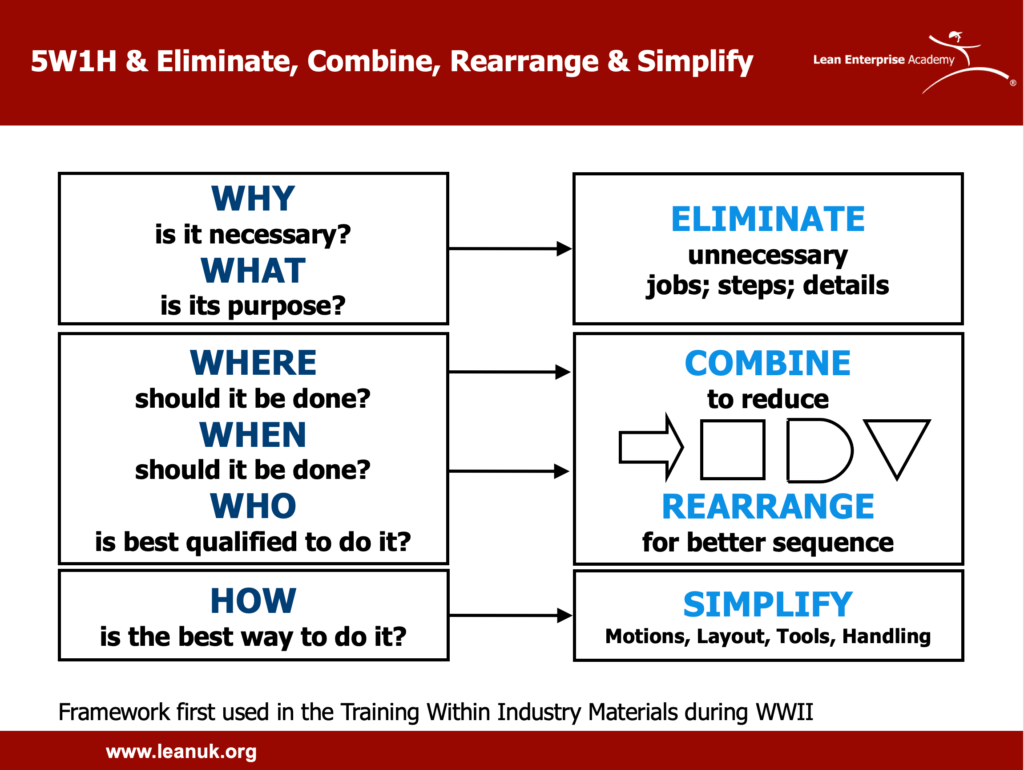

Machines, materials and layout all need to be considered. Good design in each of these areas facilitates flow. Ask if equipment can meet the takt time, how much automation we need to apply and how the layout can be arranged so one person can make one item as efficiently as possible. While we may never run the process this way, such thinking results in us challenging the boundaries in roles that we create. It also helps us think about the material management elements of getting the right items, to the right place at the right time.To achieve a flow that meets takt time, work needs to be distributed effectively and in the optimal sequence. A useful way to think about any step in the process is that it can only be eliminated, combined, rearranged or simplified. From our experience it is not unusual to be able to kaizen cycle time by 20-30% once the process is established. The extra capacity could dramatically reduce the overall lead time required to vaccinate the population.

Let’s say that a GP practice has 9,500 patients. 8,400 of them are over 18 and are eligible for the vaccine. Using the Welsh Government’s objectives of administering the vaccine by mid-February (using 14th as the finite date) to:

- Care home residents and staff

- Front-line health and social care staff

- Clinically extremely vulnerable people

- All those over 70+

You would take the total available work time of 18 days (there are 26 days from January 19th of which 18 are normal working days – we can debate whether this should be a 24hr, 7 days process, but to explain the maths that’s a separate debate.) Working 7.5 hours/day, the total available work time is 8100 minutes. If 900 patients fall into the above category, then the rate the GP surgery needs to vaccinate at is one patient every 9 minutes. As the takt time is an equation, we can adjust the inputs to get different results.

- We could change the available time to work. Increase or decrease the working day and the number of days (working Saturday or Sunday for example.)

- We could change the criteria of vaccines to be completed by mid-February (lowering or raising the customer demand.)

- We can increase or decrease the number of clinics that can do the work. For example the number of people administering the vaccine.

The thing to remember is that this isn’t the only work being done. The people administering the vaccine will already be seeing and treating existing patients.

The takt time calculation also helps us with our supply chain design as we can transmit that beat throughout it. Geography characteristics including drive time (and therefore lead time), population density and demographics are just some of the factors to be considered. However, the initial determinator to how many vaccination centres that are required is the work content to administer a jab. Work out customer demand and the process.

This logic has been used by F1 teams for over 60 years. In the 1950’s Fangio, the world champion, was stationary in the pits for almost 2 minutes while mechanics went back and forth to their garage for tools, replacement tyres and fuel. By the 1970’s Colin Chapman’s world beating Team Lotus would have Emmerson Fittipaldi pitted for 16 seconds. Today Lewis Hamilton’s Mercedes stops for less than 2 seconds on Sunday afternoon. All items are prepared, in place, with minimum movement by any of the mechanics.

The eliminate, combine, rearrange and simplify logic is equally appropriate in conducting effective vaccinations:

- Before the visit – making the booking, agreeing the appointment, preparing the patient for the process and arranging any logistics.

- During the visit – temperature checks, conducting the work in the correct sequence and with appropriate timing

- After the visit – making sure that everything is ready for the second vaccine.

Developing Capability Across the Supply Chain: Pull not Push

Designing the work involves integrating 4Ms (Man/Woman, Methods, Materials and Machines) to develop an efficient continuous flow. However, designing the supply chain arguably represents as difficult a challenge. Lean thinkers are aware that lean producers “pull” rather than “push” product through their supply chains. Push systems are those where the process upstream produces regardless of the needs of the downstream process but what does this mean when we have a start up situation and we need to fill multiple pipelines – such as GP surgeries, pharmacies and vaccination hubs? In such cases understanding the capacity (how many items we can process) in each step in the supply chain is a pre-requisite. It sounds obvious, but it is pointless delivering 500 vaccines to a GP surgery if they can only vaccinate 100 patients in a day. The other 400 vaccines would be waiting to be used.

Supermarkets realised this in the 1990’s. Our research showed Tesco the importance of delivering small quantities to each store, multiple times per day – avoiding stock outs and over stocking. Just in time has received unfair criticism from commentators that haven’t understood the concepts and underlying thinking. But regular, small lot deliveries is exactly what each supply chain node needs right now. I am reliably informed that GPs were only able to initially order vaccine supplies once per week and only receive deliveries once per week. This week the situation has been made worse as they now aren’t able to order vaccine amounts at all!

Such a situation jeopardises any effort to achieve the levels of vaccination by the desired dates. If hospitals, GP practices and pharmacies don’t know how many vaccines they will receive by when, they can only plan once they have the stock at their location. This obviously lengthens the overall lead time to vaccinate. Time is related to infection levels which are related to lives saved.

Just the pushing and batching from these systems will lead to demand amplification and who knows how much rationing and lobbying for product. Push systems operating on such long planning horizons can’t be responsive and will lead to precious vaccines being wasted – the key measure needs to be delivering the right amount of the product to the right place at the right time, right first time, on time, in less time. Daily deliveries from local hubs, rather than big batches from central stocks is critical to avoid issues and may also aid the recycling and reuse of vials for vaccine manufacturers.

Final Thoughts

All being well, the next stage of our activity will be real observation at the workplace. We hope we will have insights to make life easier for the front line and ultimately deliver the vaccine safely in a shorter lead time. No doubt this won’t be the last time we have to vaccinate – how else will we keep the vulnerable safe and revitalise our economy at the same time. The issue isn’t about ensuring people aren’t standing around and have something to do. The problem to solve is how to increase the velocity of the total process and vaccinate as soon as possible to save lives….

As a not for profit organisation, the Lean Enterprise Academy was established to help customers become self-reliant on their lean journey. Through research, products and services we provide better, faster and cheaper ways to learn and improve. If you would like any help and support on some of the points raised in your organisation e.g. problem solving, kaizen, standard work, value stream mapping, please do not hesitate to contact us.