How the A3 Came to Be Toyota’s Go-To Management Process.

by Isao Yoshino

August 2, 2016

The discussion below between John Shook and Isao Yoshino first appeared on The Lean Enterprise Institute website www.lean.org.

As context, John Shook defines the A3 process as “… the A3 is a visual manifestation of a problem-solving thought process involving continual dialogue between the owner of an issue and others in an organisation. It is a foundational management process that enables and encourages learning through the scientific method.” pp11 of Managing to Learn

Understanding A3 Thinking has evolved over time. In 2016, John said he would change the term “scientific method” to “scientific thinking” in that definition because the scientific method is but one of a number of ways of structuring to do science. In addition, John clarified that the A3 process is a process to help teams do science together. It’s much more than a structure for a problem solving process – it can become a way of enabling people to work together effectively.

The history of the A3 process provides context. Context to the “problem(s)” Toyota was attempting to solve by developing such a process. You may not have exactly the same problems as Toyota did when it started its journey, but we are sure any organisation will be more successful if they are deliberate in the development of management skills, capability building and thinking. It’s not enough just to hire great people, we need to build capability and behaviours over time.

We hope you find that this interview helps you think through why developing such processes are so important.

In the late 1970s, Toyota decided to invest in cultivating the managerial capabilities of its mid-level managers. Masao Nemoto, the same influential executive who led Toyota’s successful Deming Prize initiative in 1965, led a development program especially for non-production gemba managers called the “Kanri Nouryoku Program” – “Kan-Pro” for short. Nemoto chose to structure this critical management development initiative around the A3 process.

The A3 is well established now in the lean community. As a process, as a tool, as a way of thinking, managing and developing others. The question often comes up of where did it come from and how did it become a common practice. The basic answer is that it dispersed mainly from Toyota. But how did it become so prevalent in Toyota? And how did it evolve from its humble beginnings as a tool to tell a PDCA quality improvement story on an A3-sized sheet of paper, as it had been commonly used by many Japanese companies since the 1960s?

What had started as a simple tool to tell PDCA stories grew at Toyota into something more: the A3 process came to embody the company’s way of managing in an extraordinarily profound sense. How did this happen?

My first “kacho” (manager) at Toyota (in Japan starting in 1983), Mr. Isao Yoshino, was a member of Nemoto’s four-man team that created and delivered the “Kan-Pro” manager-development initiative that directly answers that question. The program has been unknown outside Toyota … until now.

—John Shook

Interview with Mr. Isao Yoshino

Q: What was the purpose of the Kanri Nouryoku Program?

A: The main purpose was to nurture “Management Capabilities” of employees who were at manager (kacho) level and above. There were four rudimental capabilities for managers:

- Planning capability, judging capability

- Broad knowledge, experiences and perspectives

- Driving force to get job done, leadership, kaizen capability

- Presentation capability, persuasion capability, negotiation capability

Q: Why did Toyota decide it needed this program?

A: After introducing Total Quality Control (TQC) in 1961 and receiving the Deming Prize in 1965, TQC-based perspective had taken root widely across the company. In the late ‘70s, Mr. Nemoto (one of the main people behind launching TQC) noticed that management capabilities and TQC awareness was decreasing among managers, particularly within the non-manufacturing gemba or office divisions. Mr. Nemoto decided to take actions to reinvigorate the managers (especially administrative) and help heighten awareness of their role. And so, in 1978, he formed a task force that promoted a two-year program (the Kanri Nouryoku Program) for two thousand managers from all over the company. I was one of the four staff members on the task force in Toyota City.

Q: What sort of tools and activities did the Kanri Nouryoku employ?

A: All the managers went through “a presentation session” twice per year (June and December). The officers in charge of each department attended to have a Question and Answer session with the managers. Officers tried to focus on the problems each manager was facing as well as the effort and process needed to solve the problems. Officers focused more on “What is the major cause of the problem?”, rather than “Who made those mistakes?” This problem-focused attitude (as opposed to the who-made-the-mistake attitude) of the officers encouraged managers to share their problems rather than hide them.

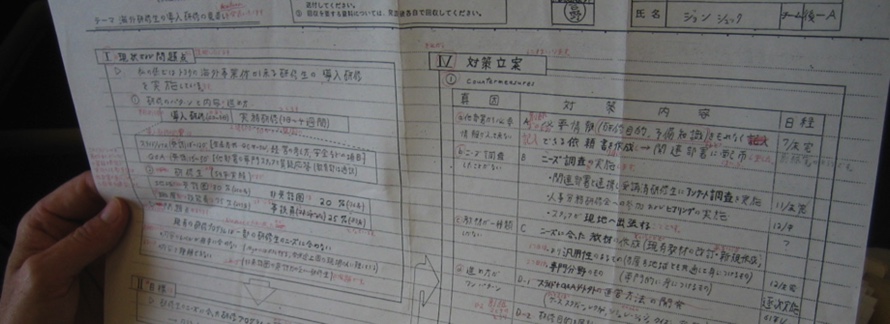

The key to giving the presentations was that they had to be done using an A3. The managers learned how to select what information/data was needed and what was not needed, since an A3 has only limited space. This helped them acquire the seiriand seiton functions of the 5S concept as applied to knowledge work. A3 was also a great tool for officers. They could easily see, at a glance, all the key points that the presenter wanted to convey. As it is just one single document, you can quickly see from the left top corner to the right bottom of an A3 and grasp the key things the writer wants to communicate. This is something that you cannot get from a written document or PowerPoint presentation.

Q: What was your personal experience with the program?

A: First, I was fortunate to get acquainted with many admirable managers, who inspired me in many ways. I also learned how to express myself more effectively by studying A3 documents from two thousand managers. Strikingly, I discovered that managers whose A3s were excellent were also excellent managers at work.

Nemoto-san highly praised managers who took a risk to report their mistakes (not success stories) on A3s with a hope of finding a solution. Nemoto valued their sincere and proactive attitudes. “Nemoto Lectures” were held for managers three or four times a year. Mr. Nemoto went through every single impression memo from the audience as feedback for his next speech.

Mr. Nemoto also appreciated the efforts by managers who tried to nurture excellent subordinates. This created a new company-wide notion that “developing your subordinates is a virtue.” It was amazing to see managers in their 40s and 50s willing to give 100 percent of their energy to work on hoshin kanri and A3 reporting, because they were convinced the program was practical and useful and worth using to bring themselves up to a higher level. Seeing all this happen at work truly helped me grow professionally.

Q: What was the effect of the program on Toyota?

A: Well for one, every mid-level manager who was involved in this program over the two years came to clearly understand their roles and responsibilities and also learned the importance of the hoshin kanri system. People at Toyota don’t hesitate to report bad news, which has been Toyota’s heritage since day one. The Kanri Nouryoku program has further reinforced this tradition because of its praise toward managers and others who were honest about their mistakes. And after the program was implemented to the back-office managers, the level of their awareness of their role rose up to the same level of that of manufacturing-related managers, which significantly strengthened the management foundation.

Everybody became familiar with using the A3 process when documented communication was needed – A3 thinking eventually became an essential part of Toyota’s culture. People learned how to distinguish what is important from what is not.

Isao Yoshino

Lecturer, Nagoya Gakuin University

Isao Yoshino is a Lecturer at Nagoya Gakuin University of Japan. Prior to joining academia, he spent 40 years at Toyota working in a number of managerial roles in a variety of departments. Most notably, he was one of the main driving forces behind Toyota’s little-known Kanri Nouryoku program, a development activity for knowledge-work managers that would instill the A3 as the go-to problem-solving process at Toyota.

Now move onto the next Topic